A Cor de Coimbra

O mercado:

It's morning, and I'm hungry

I head to a place in Coimbra that still lives in the past century, where time seems to pass but never takes it along. I arrive at the market—or rather, at María's. Coimbra's municipal market is as old as its first day, except for a few elevators and escalators that, depending on people's moods, go up or down.

María started working there 47 years ago with her sister. She laughs, recalling how she used to carry fruit in a basket on her head. It's a small time capsule—she knows everyone, has seen generations grow, trees surpass 50 meters, and students return just to say hello. She was thrilled when the escalators arrived. That day, they were going up, perfect since she had to take the fruit upstairs. She enjoys her little shop, A Lindita, chatting and selling her goods. Fridays, she says, have the most variety.

I bought some bananas, the color of the city, in a small fruit shop, in a market from another century.

O baloiço

1.- Preludes to reach a baloiço

First, after eating something (though it's also a good idea to bring food with you, depending on the experience you seek), we begin walking uphill—unless, of course, we're already at the top.

No need to worry about this, as Coimbra is a constant up-and-down. We can wander around until we find a direction that feels right, and then we'll try to walk in a straight line for a good while (about 30% until we're tired). After that, we'll veer 20 meters to the right and continue straight.

At some point, we'll see a large sign that says something like “visit,” and that's the signal we've been waiting for. As if that weren't enough, a second, smaller sign will be even clearer. The arrow points to the place.

2.- What should catch our attention?

From my experience, I found three essential things to discover at a baloiço. The first was the baloiço itself, guarded by a few warriors the size of a cat, and shaped like one.

These cat-shaped guardians will approach to check your intentions and will mark you with their scent, so the other warriors know you are welcome. Once you pass this test, you'll meet other beings of the moment. They tend to shift as silence and words lose their meaning.

I share my experience

I met André, André, a nurse from Lisbon with a student past there. Last year, he immersed himself in a humanitarian mission in El Salvador, where he met María.

Who is María? María is a psychologist from Seville, with the same humanitarian mission. It was in El Salvador where she met André.

Who introduced them? The Narrator. The Narrator met them at a place called "o baloiço," a swing on a viewpoint with city views. He met them as randomly as they found the place itself. They stopped there to see, to find peace, in the "oasis of Portugal," the end of a journey.

After being interrupted by a narrator with a camera and many vague questions, they left, just like the Narrator did, leaving behind in “o baloiço” the views of Coimbra, a color between ochre and dark green, in the eyes of anyone who observed.

Oliveira

I'm not sure if I crossed paths with a person from another time, or from another fantastical reality. This aging figure, with lips that never seemed to move, spoke to me as though I were the last person to hear their words, preserving them for years so they wouldn't die. And when my time came, perhaps I'd repeat the process—or maybe I misunderstood everything.

I found myself speaking with someone (Oliveira) as strange as he was, yet more intelligent than himself. A sort of lawyer specializing in hospital administration and a delegate for the ministry of blah blah... A careless type, but not careless, a bit crazy, yet surprised to learn how little madness can taste, until it bores you.

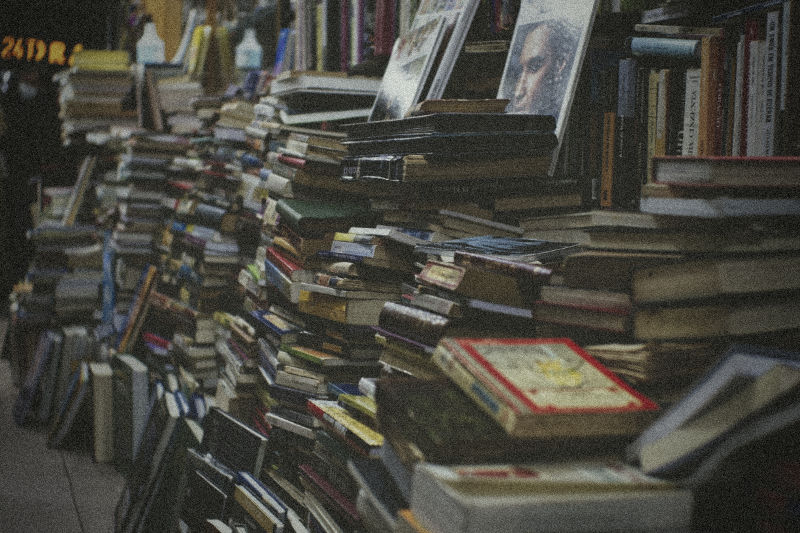

Oliveira has maps, some ceramics, and ink. Ink in the form of small doodles with rounded edges, some with tails, others without, all aligned horizontally, trying to trace paths across the pages from end to end. He is the son of the ignorance of being ignorant. His shop is one of the smallest, yet the largest on the inside. If we counted the world hidden in his trinkets, we’d realize there’s more world than what’s drawn on the maps, and more time than what’s real.

There’s a Latin word: “otium,” which in my story means unpaid intellectual activity, the opposite of “nec-otium,” which ends in profit. Otium and Nec-otium are antonyms. The shop run by that strange man isn’t a business, it’s leisure—a cover to collect books, ceramics, maps, photos, music, and objects so strange they can’t be described in one language.

What Oliveira shares is not just knowledge. I’m not the first nor the last young person to teach how to start a flame. It's different from having it lit for you—one day, it might go out.

We met in Coimbra. Or I met him in Coimbra, I’m not sure.

For those who don’t know what Coimbra is:

“Coimbra is a song, of dreams and students, of tradition and love, in Portugal.”

O Lino

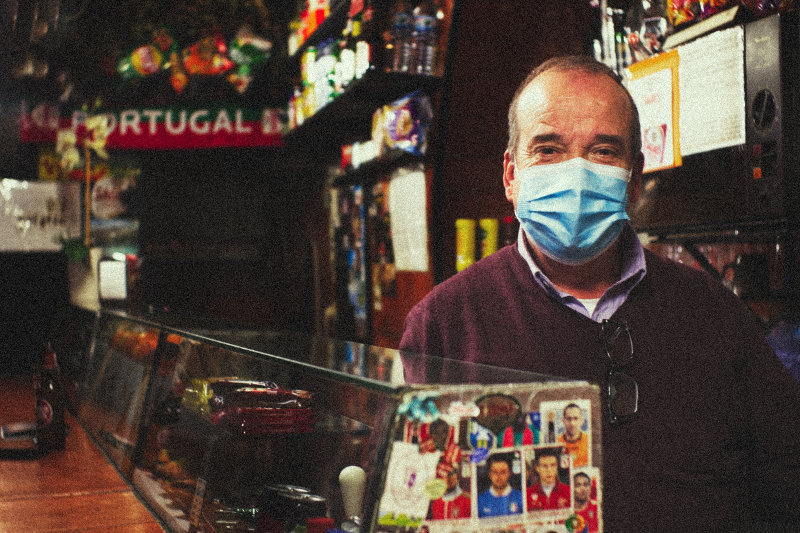

Night falls, and my stomach growls for food. I know where to go.

For 33 years, O Lino has run a small bar hidden between the “Sé Velha” and Coimbra's tourist street. It’s at the end of a steep, stair-filled street, where we find a tiny door revealing his bar. While you choose between a bifana or "tosta de bacalhau," O Lino introduces himself.

“In all the time behind a bar, you see how things change around you. This city, once a town, is now an international village led by students of every nationality.”

His tavern, “a Tasquinha,” is a small, intimate space, where conversations start without you even noticing.

O Lino is a kind local who loves Coimbra. Through his eyes, we see an ancient Coimbra, a twist on the contemporary, with a pink hue like that of "Queen Santa Isabel" in Portugal.

Music for Two or More

It's strange to walk the street at night and only hear voices or footsteps. It means the street is silent. No music tonight? I begin to worry.

Wait, I think I hear something in the distance. I feel at ease.

From this point, a musician sings, or maybe two. From other points, more voices join. On the benches, two (or more) sit in silence, not disturbing the solitude with words or smoke. The wind guides the smoke toward the music, inspiring the musician to sing a song he thought he had forgotten, revived two nights ago by a Frenchman’s ringtone in a bar he won’t return to, for it was served cold. He starts to pour his feelings into the words, in English with a Portuguese accent, a song that enchants two (or more) people.

( PARENTHESIS )

I open a parenthesis at the end of this day, like a special mention or a public award in a contest.

I want to share the photos that never became big stories, or at least not “told ones.”

They align with Coimbra and its colors, this time more abstract and warm.